Determinants of sustainability reporting in the present institutional context

Determinants of sustainability reporting in the present institutional context: the case of seaport authorities

1. Introduction

Across industries and geographies, stakeholder pressures have created an environment in which a successful corporate strategy is defined by and dependent on the integration of strategic objectives related to environmental and social challenges for which organizations are held accountable. In response to this overall greater awareness and concern about an organization’s activity and related positive and/or negative effects, businesses have engaged in various sustainability initiatives, e.g. sustainability reporting, to monitor and tackle the existing issues. Open communication and transparency are nowadays key aspects in the process of enhancing the organization’s accountability. Hence, “accountability involves the responsibility to undertake certain actions and the responsibility to provide an account of those actions” (Moneva, Archel & Correa, 2006, p.126). However, as stated in the research of Adams (2002), collecting environmental data is not directly connected to the systems for collecting economic data, confirming limitations to mere financial reporting. Therefore, the field of accounting for more integrated performance has been developed, in particular that of sustainability reporting, which goes beyond financial/economic reporting, but also includes the other two aspects of the Triple Bottom Line (TBL): information related to environmental and social performance. Disclosing sustainability related information through a sustainability report (SR) can be regarded as an important strategic key element to foster trust, loyalty and confidence from different stakeholders, as a SR can serve as proof that an organization accounts for more than just profitability (Herold, 2018). In the mainstream business literature, a significant amount of research has been conducted in terms of identifying the motivations and drivers to engage in sustainability reporting (Adams 2002; Bebbington, Higgins & Frame, 2009; Herzig & Schaltegger, 2006; Thijssens, Bollen & Hassink, 2016). The organizational practice itself remains mainly voluntary (Hahn, Reimsbach & Schiemann, 2015), leaving room for experimenting on what to disclose and which guidelines to use. The Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) is at present the best-known and generally accepted framework offering guidelines for the practice; it was founded in light of standardizing and improving comparability of SRs on a global level (Brown, de Jong & Levy, 2009). However, in spite of these convergence efforts, comparability between SRs is still often limited because of differing external (institutional environment) and internal (organizational characteristics) factors (Hahn & Kühnen, 2013; Herzig & Schaltegger, 2006). A good understanding of both internal and external determinants is necessary in order to further improve the development of sustainability reporting frameworks and diminish the variations in the global use of it.

Despite a rapid increase in attention for and importance of sustainability reporting in many industries, its value has not been fully recognized by the maritime industry, and ports in particular. Also, academic research on the topic remains rather scarce and in an emerging phase (Ashrafi et al., 2019; Vejvar et al., 2018). Exploratory research based on a content analysis of ten SRs of leading seaport managing bodies, all based on the GRI framework, revealed that significant differences exist at the level of indicators reported, boundary levels of reporting, as well as stakeholder inclusion in the process (Geerts & Dooms, 2017). Building upon this research, this chapter contributes with new empirical insights to this emerging field through the identification of the internal and external factors that positively/negatively influence the practice of sustainability reporting by PMBs on an international level.

We start by reformulating determinants identified in existing literature across industries (Brammer & Pavelin, 2008; Monteiro & Aibar-Guzman, 2010; Fifka, 2013; Hahn & Kühnen, 2013; Kouloukoui et al., 2019; Tagesson et al., 2009; Thijssens et al., 2016) and adapt those to the specific context of ports. We also add a newly defined determinant ‘sustainability integration’ that tries to capture the extent to which sustainability in all its aspects is part of the ‘organizational DNA’. The internal determinants are defined by the PMB’s characteristics, whereas the contextual factors are defined by the environment and society to which the PMB is contingent. In order to explain the contextual forces influencing the initiation of sustainability reporting, we apply institutional theory. Across different domains, this theory has already proven its validity as it leads to a better understanding of the dynamics independent of strategic analysis in sustainability decision-making (Husted & Allen, 2006; Tavares & Dias, 2018). With regard to seaports, the application of this theory has been very limited (Acciaro, 2015; Geerts, Langenus & Dooms, 2017; Santos, Rodrigues & Branco, 2016). This chapter not only adds value to the literature by making use of the institutional theory as explanatory basis, but also by applying those theoretical insights to real empirical data in order to (in)validate existing assumptions.

Collecting data has been accomplished by making use of an online survey that has been developed in direct collaboration with the International Association of Ports and Harbors (IAPH). Hahn and Kühnen (2013) reveal in their literature review of 178 articles related to sustainability reporting as a practice in business, management and accounting research that only in a scarce 4% of those papers a survey technique has been used. Furthermore, 58% of the analyzed papers are based on document analyzes showing a general deficit in both exploratory and confirmatory approaches. By applying the survey technique, we were able to conduct an analysis with a higher level of managerial-driven psychological depth than most analysis based on content-analysis. It is the first study that generates broader institutional insights based on real answers of port managers and links these with the results of a regression analysis in order to maximally reveal the driving mechanisms behind sustainability reporting in the port sector. The results in this chapter do not show individual cases, as responses are processed on an anonymous basis and in strict confidence. In brief, our analysis contributes to the existing literature in several ways: 1) there is not much known about sustainability reporting by PMBs on a global scale, 2) the incorporation of all already existing determinants into one large model as well as the identification of a new determinant ‘sustainability integration’, 3) the use of a survey, 4) applying institutional theory based on real empirical results.

The chapter is structured as follows: Section 4.2 provides an overview of identified determinants that have a positive/negative influence on the initiation of sustainability reporting. For each determinant the specific context of PMBs will be discussed. Section 4.3 positions the institutional theory in the context of ports and explains the institutional forces to which PMBs respond. Section 4.4 discusses the methodology. The analysis and discussion of the results will be provided in Section 4.5, which will be divided into two subsections, each focusing on a separate research question:

• What are the determinants influencing the practice of sustainability reporting in the context of PMBs?

• Which organizational characteristics and institutional pressures emerge together and play a role?

The chapter concludes with some managerial implications, limitations of the research as well as suggestions for future research.

2. Determinants influencing sustainability reporting

The most well-known benefit of sustainability disclosure is that of reducing information asymmetry between the organization and its stakeholders, inducing no room for speculations and thus diminishing the overall risk level of the organization (Cormier & Magnan, 1999; Brammer & Pavelin, 2004; Brammer & Pavelin, 2008). However, even with the knowledge of the advantages of sustainability reporting, still many organizations choose not to start developing a SR. The main identified reason relates to organizational costs linked to the disclosure of sustainability information: “the costs of measuring, verifying, collating and publishing environmental information, and the loss of strategic discretion associated with making public commitments to verifiable future actions and/or performance” (Brammer & Pavelin, 2008, p.122).

As stated by Cormier and Magnan (1999), decisions made with regard to defining a sustainability disclosure strategy will always be the result of a cost-benefit assessment (sometimes intrinsic). Decision-making in light of sustainability disclosure is therefore expected to depend upon a range of organizational and environmental aspects that influence the benefits and costs (including opportunity costs) of disclosing such information. For some organizations sustainability reporting will be more costly than others. Through the years, and across various industries, countries, and institutional environments, several internal and external determinants, respectively organizational characteristics and contextual factors, have been identified as significant explanatory variables to clarify the initiation and existence of sustainability reporting (Brammer & Pavelin, 2008; Cormier & Gordon, 2001; Fifka, 2013; Hahn & Kühnen, 2013; Kolk, 2004; Kouloukoui et al., 2019; Monteiro & Aibar-Guzman, 2010; Naser et al., 2006; Tagesson et al., 2009). We selected those variables that would also apply to the port industry and adjusted them to the specific context of PMBs. Furthermore, we also added variables not often investigated in literature, e.g. number of social/environmental certifications, and a newly defined one, i.e. sustainability integration. Other variables did not make the selection because of data availability reasons as we wanted to keep the survey as clean and appealing as possible to maximize the response rate. In the analysis that follows, we start by reformulating the selected determinants in light of the context of the port industry and try to detect to which extent they apply to PMBs.

2.1 Size and organizational visibility

The assumption that there is a positive relationship between the size of an organization and the level of sustainability disclosure has been analyzed and confirmed by multiple studies over the past decades (Brammer & Pavelin, 2004; Brammer & Pavelin, 2008; Hahn & Kühnen, 2013; Kouloukoui et al., 2019; Monteiro & Aibar-Guzman, 2010; Naser et al., 2006; Prado-Lorenzo, Gallego-Alvarez & Garcia-Sanchez, 2009; Tagesson et al., 2009). Several arguments exist in support of this positive correlation. Firstly, in general, larger organizations occupy spotlight positions which causes their activities to be more visible for the public, external agents, governments, etc. In this way, they are also exposed to a higher degree of attention from stakeholders in relation to their sustainability efforts, translated into greater pressures (Brammer & Pavelin, 2008). Secondly, as those larger organizations are monitored by the public eye, they are expected to handle in a way that benefits society. In order to limit those external pressures, they are more quickly willing to voluntary disclose information (Kouloukoui et al., 2019). Thirdly, as mentioned above, the preparation and disclosure of Triple Bottom Line information is costly. Compared to small and medium-sized organizations, larger ones possess the necessary resources (financial and human) to collect, analyze and report data (Monteiro & Aibar-Guzman, 2010; Naser et al., 2006).

Research of Ashrafi et al. (2019) shows that the same reasoning holds in the context of ports. The adoption of sustainability initiatives seems to be correlated with the size of the port, as most small and medium-sized ports did not adopt any sustainability measure, probably explained by the expenses linked to it. Hence, the related hypothesis is stated as follows:

H1: There is a positive relationship between the size of the PMB and the production of a SR.

2.2 Financial capability

Several studies have looked at the possible association of an organization’s financial performance and the disclosure of TBL information (Hahn & Kühnen, 2013; Kouloukoui et al., 2019; Monteiro & Aibar-Guzman, 2010; Tagesson et al., 2009). A higher level of financial performance in terms of the availability of economic means is often associated with a higher level of power, translating in a higher level of stakeholder pressure. Being in a good financial condition increases the ability and flexibility to bear costs that are linked to investments in sustainability initiatives of which sustainability reporting is one (Hahn & Kühnen, 2013) as well as costs linked to revealing potentially damaging information (Cormier & Magnan, 2003). It is therefore expected that organizations with a higher financial capability will more easily disclose TBL information to differentiate themselves and minimize the possibility of adverse selection (Akerlof, 1970).

Research conducted by Kuznetsov et al. (2015) shows that small ports are not very willing to invest in environmental management systems as this causes a burden in their net profit. Small and medium-sized ports often mention a reduction in profits or at best make reference to a break-even situation when it comes to investments in sustainability actions (Ashrafi et al., 2019). However, financial capability as a separate variable in the analysis of sustainability reporting by PMBs has not been researched before. In our study, we will use financial turnover to define this variable as a proxy for ‘the availability of economic means’, as there is currently no commonly accepted indicator for financial capability under the form of e.g. profitability for PMBs due to, inter alia, different governance frameworks and/or PMB business models.

H2: There is a positive relationship between a PMB’s financial capability and the production of a SR.

2.3 Country / region

Countries are characterized by different legal frameworks, national culture and behavior. The question is if these variations will be reflected into the practice of sustainability reporting. Some countries, e.g. Sweden and continents, e.g. EU have chosen to enact some ground rules as well as binding policies with regard to sustainability reporting (European Union, 2014; GRI, 2010). Besides the legal environment in which organizations operate, also the national culture of a country, not only in terms of history and tradition, but also in terms of moral values, can influence the decision-making and handling of organizations. Prevailing moral values shape the ethical behavior of an organization and thus have an influence on the issues an organization select as being worthy for resource allocation (Adams, 2002).

Research of Santos et al. (2016) indicates that the national context in which the PMB operates plays a role in the existing variety when it comes to sustainability communication. Also, previously conducted exploratory research, based on a content-analysis comparison of SRs of ten different leading PMBs, shows country dependence differences (Geerts & Dooms, 2017). For this reason, we define the following hypothesis:

H3: The region of origin has an influence on the practice of sustainability reporting by PMBs.

2.4 Level of autonomy

Only a limited amount of extant literature has analyzed the impact of different ownership structures, i.e. private vs. public, on the disclosure of environmental and social information (Cormier & Gordon, 2001; Naser et al., 2006; Tagesson et al., 2009). According to Santos et al. (2016), when looking at possible determinants for sustainability disclosure, integrating information on ownership structures has not been applied for the port sector. Nevertheless, the situation of PMBs regarding their ownership structure is very complex and thus interesting to investigate in this context. While the ownership structure of a PMB is often considered as a hybrid structure as the shareholders can be a mix of the public and private sector, in most cases the ownership structure does not provide a clear representation of the actual level of autonomy of managerial decision-making. This means that while many PMBs act like limited liability companies with varying executive power, they have the obligation to report back to their private and/or public shareholders, i.e. local, regional and national governments (Pallis, 2007; van der Lugt, Dooms & Parola, 2013). In general, because of this hybrid nature, PMBs are confronted with substantial public-private interactions and interests both on a daily basis and in longer-term strategic decision-making, showing the need for good and transparent communication strategies in order to stay evolving towards the same objective (Notteboom et al., 2015). This, in extension, also applies to decisions related to the adoption of sustainability practices, as an increased level of autonomy will also increase the accountability of port managers. In light of the specific context of ports we formulate the following hypothesis:

H4: There is a positive relationship between the level of autonomy of a PMB and the production of a SR.

2.5 Stakeholder inclusion

In recent decades, a wide array of research already pointed out the need for multidimensional information when it comes to sustainability reporting compared to the traditional financial reporting as also the audience is not limited to only shareholders (Belluci & Manetti, 2019; Deegan & Rankin, 1997). Various salient stakeholders (clients, government, local community, etc.) demand a clear view on an organization’s business conduct taking account of all TBL domains (Hahn & Kühnen, 2013). As stated by Bellucci and Manetti (2019, p.92):

“Dialogue with stakeholder groups is essential for sustainability reporting because it enables organizations to create truly material and relevant reports about the true creation of value for all stakeholders”.

This dialogue can entail different degrees of involvement and models, in the range of no or limited inclusion (informing, one-way dialogue) to full inclusion (majority of stakeholder representation in the decision-making). However, some authors claim (Campbell, 2003; Hess, 2008) that to date organizations use stakeholder inclusion more in an opportunistic manner as being a legitimation tool to change stakeholders’ expectations. Therefore, we believe that the lower the level of stakeholder inclusion, the greater the chance a SR will probably only have a mere legitimacy purpose. The opposite reasoning holds as well: the higher the level of inclusion of stakeholders, the more the organization wants to achieve a consensus of stakeholders’ needs and expectations, to be reflected in a SR. Only when stakeholders are consulted to a high degree and on an ongoing basis, the content of a SR is not only showing what the focal organization believes its stakeholders want to know but will also show those issues (positive and/or negative) that are regarded as material by the stakeholders themselves. Research of Geerts and Dooms (2020) shows the importance of good and open communication between an organization and its stakeholders, as results show that what is material for stakeholders is not always supported to the same extent by the focal organization, and this also counts for the underlying reasons why organizations (should) produce a SR (Kolk, 2004).

In the specific context of ports, the approach towards proper stakeholder inclusion is even more complicated because of the prevailing hybrid ownership structures and the variety of involved stakeholder groups with all showing different (sometimes conflicting) objectives (Dooms, 2019; Geerts & Dooms, 2020). Port managers are increasingly aware that disclosure should consist of a range of diverse topics, tailored to the needs and demands of each individual stakeholder group in order to reduce the risk of information asymmetry.

H5: The higher the level of stakeholder inclusion in general strategy formulation the more chance a PMB will publish a SR.

2.6 History of performance data gathering

For several decades, organizations are obliged to disclose information on their financial/economic situation, translating into a certain (minimum) need of data collection and analysis. However, with the increase in importance of social and environmental aspects linked to the business activities (Lozano, 2013) and the associated reporting, this also calls for a more holistic and comprehensive approach regarding the data gathering efforts of organizations. Unfortunately, most of the data and information related to social and environmental aspects cannot be found in the public space, as it concerns tailored information. The process of data gathering and analyzing requires time, resources and sometimes proprietary and tailor-made build-in measuring models. These challenges are exacerbated in the context of PMBs, as they often rely on external stakeholders for data collection in order to gain insights in the impacts of the operations of the port cluster (Langenus & Dooms, 2015). We believe that when an organization is willing to invest in collecting and analyzing data beyond the necessary, this also indicates that the organization is willing to commit supplementary resources with regard to sustainability initiatives, of which sustainability reporting is an important one. Tangible efforts oriented to data gathering and the associated performance reporting all together provide the impression of caring as the organization tries to keep track of its progress on all the Triple Bottom Line domains. Vice versa, if an organization is not willing to invest, or maybe not able to collect extra information because of resource barriers, this will negatively influence the potential of producing a SR.

H6: The more there is a history of performance data gathering as part of the general corporate strategy the higher the chance a PMB will publish a SR.

2.7 Proximity to the city

Research of Adams (2002) shows that organizations with head offices on site are paying more attention to the ‘well-being’ of local communities compared to organizations that do not have their head offices on site. For the latter, shareholders and employees are the most important stakeholders for whom a traditional financial report is often enough. The same logic holds for the port industry. According to Darbra et al. (2004), the available space between ports and cities, i.e. proximity between both, influences corporate social responsibility behavior of the PMB as it constitutes a variable in the construct of potential stakeholder conflict. Reporting practices can be regarded as partial response to the need for intense stakeholder interaction to manage expectations of and disagreements with the local community (Belluci & Manetti, 2019). We believe that the closer a PMB is located to densely populated areas, the larger its visibility will be, the higher the importance of local communities as stakeholders and thus the larger the role a SR can play in contributing to the support for port activities. For these reasons, we formulate the following hypothesis:

H7: There is a positive correlation between the proximity of a PMB to a city and the publication of a SR.

2.8 Environmental and social certifications

At present, various standards, codes and schemes, both on the general and industry specific level, have been developed to certify a port’s environmental and social performance (ISO 14001, ISO 26000, PERS, GreenMarine, etc.) all promoting and contributing to better sustainability practices. Organizations often strive to reach compliance with several standards as this signifies a part of their strategic posture, meaning to strengthen their ‘sustainable’ image towards their stakeholders. Those certificates are means of proof that the organization is willing to differentiate itself from its industry peers, through an independent auditing of their adherence to and application of social and environmental management procedures. After literature review, no other study in the domain of ports has considered this variable as potential determinant of sustainability disclosure. The hypothesis is formulated as follows:

H8: There exists a positive relationship between the number of environmental/social certificates/labels a PMB has obtained and the production of a SR.

2.9 Sustainability integration

The concept ‘sustainability’ goes beyond pure environmentalism. Not only refers it to safeguarding the natural systems and resources, it also comprises the principles of social equity and economic development. Sustainability stands for acknowledging that these different aspects do not work as stand-alone mechanisms but are parts of a larger global perpetual system. Translating this into an approach on the organizational level is a complex undertaking as it requires a proactive attitude towards sustainability at multiple levels throughout the organizational structures and systems. Many individual initiatives in the context of sustainability can be undertaken by organizations and provide an indication on the amount of invested effort. However, a long-term commitment to sustainability requires economic, environmental and social considerations being regarded as part of the core business activities of the organization as well as being supported by and reflected in the organizational culture, i.e. through norms, values and beliefs (Bonn & Fisher, 2011; Oertwig et al., 2017). If steps and actions towards sustainable development are undertaken, organizations will always make sure that these improvements will be communicated to the public as not only the actions on their own but also the transparency about these actions have benefits such as, among others, building trust and loyalty, and improvement of stakeholder relations (Borga et al., 2009). One of the communications means that gains in importance is a SR, as it serves as a complement to the financial report, showing longer-term commitment to sustainability.

We believe that the amount of sustainability initiatives an organization implements and the degree of integration across organizational levels is an indication of the extent to which sustainability is incorporated into the ‘organizational DNA’ and thus will also indirect influence the willingness to develop a SR (Ashrafi et al., 2019). Therefore, we formulate the following hypothesis:

H9: There exist a positive relationship between the extent to which the concept ‘sustainability’ is incorporated into the organizational DNA and the production of a SR.

3. Institutional framework

In Section 4.2, we identified several external (organizational size, financial capability, ownership structure, country, proximity to a city) and internal (stakeholder involvement, environmental certification, own variable) organizational explanatory variables for the initiation of sustainability reporting by an organization. However, organizational activities are also subject to contextual factors, conditioned by the ‘field’ in which they operate (Powell & DiMaggio, 1991).

“Fields are best understood as the center of dialogue and interaction, through which a diverse range of institutions come to bear on field participants, and influence common organizational behaviors and their rationality” (Bebbington et al., 2009, p.593).

However, conditioning effects of the same ‘field’ or institutional environment can also only partially justify the differences that exist concerning the initiation of sustainability reporting. In contrast to existing literature that often only looks at one of the two approaches (Adams, 2002; Bebbington et al., 2009; Higgins & Larrinaga, 2014; Kouloukoui et al., 2019), it is the combination of both, corporate characteristics and contextual factors, that allows an unveiling of the driving mechanisms behind the practice of sustainability reporting.

Following the institutional theory, organizations are confronted with institutional pressures in the form of mandatory provisions (cognitive isomorphism), behavioral standards (mimetic isomorphism), individual morality (normative isomorphism) and the eager to reach competitive advantage (competitive isomorphism), often occurring as a combination of several and pushing organizational behavior to a certain homogenous objective defined by the ‘field’ at issue (Li et al., 2019).

• Coercive isomorphism – formal and informal pressures from governments and other social forces, i.e. stakeholders, with the threat of punishment when not respecting. In the case of the port industry, this can be revealed through regulations, laws, and rules (e.g. IMO International Standards) or powerful stakeholder relationships (e.g. terminal operators, shipping lines, etc.).

• Normative isomorphism – transferring of norms and values through methodologies, models, standards and practices developed and diffused by professional networks or formal education. The GRI and Ecoports are two examples of voluntary-based standards and codes of conduct that promote sustainable development in (maritime) organizations.

• Mimetic isomorphism – organizations tend to copy the actions of successful and more legitimate counterparts. In order to overcome bounded rationality and uncertainty, PMBs often choose similar sustainability practices as their frontrunners in the domain e.g. the growing institutionalization of the landlord model.

• Competitive isomorphism – in order to accomplish competitive advantage, organizations will cross traditional boundaries, for example those of traditional reporting. Sustainability reporting can have a positive effect on a PMB’s stakeholder relationships and thus can lead to superior performance.

As stated by Herold (2018, p.9), “the key message of isomorphism is that organizations with similar institutional pressures will eventually adopt similar strategies or logistics to gain legitimacy”, as for example sustainability reporting. However, the explanation behind the institutional theory neglects the heterogeneity of organizational behavior within the same ‘field’ (Herold, 2018). It is when the ideas and beliefs proper to the institutional theory are combined with the information on internal and external organizational characteristics (Section 4.2), that a rather complete image of the situation can be painted. Based on this knowledge we formulate a supplementary research question focusing on the existing heterogeneity of organizational behavior of PMBs when it comes to SR adoption: Which organizational characteristics and institutional pressures emerge together and play a role under which conditions? This understanding will allow academics as well as practitioners to develop new frameworks and guidelines, more adapted to the features and needs of the port industry and its players.

4. Methodology

As the objective of the study is to establish a better understanding of the practice of sustainability reporting and how it could be promoted in the industry worldwide, we sought for the views of global experts who are active in PMBs and possess knowledge on and are involved in the decision-making processes in the areas of sustainability, strategy and performance of the PMB. To obtain our objective we worked in close collaboration with the International Association of Ports and Harbors (IAPH).

4.1 Research construct

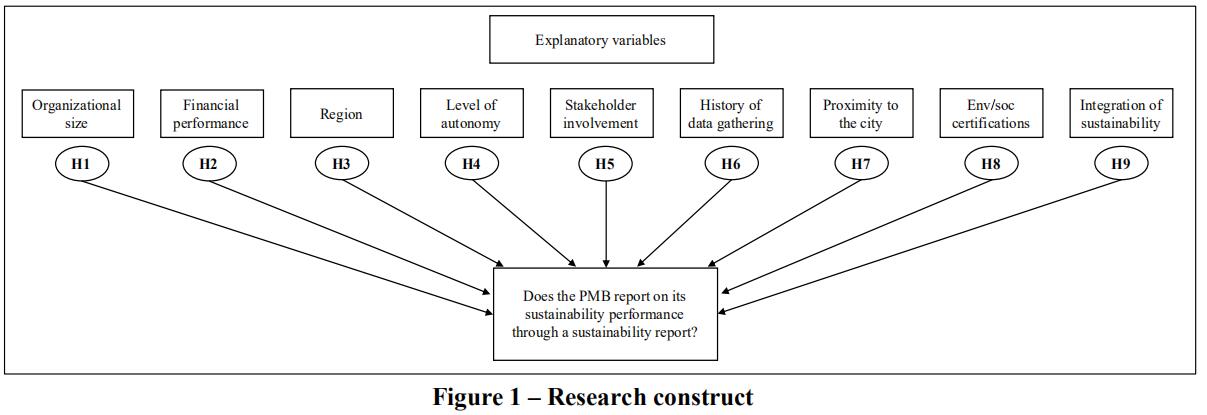

We divide the research into two large sections each based on one of the posed research questions: 1) What are the main determinants influencing the practice of sustainability reporting in the context of PMBs? 2) Which organizational characteristics and institutional pressures emerge together and play a role under which conditions? The first section of the analysis is based on the research construct shown in Figure 1.

In the literature review of this chapter we investigated and defined all variables that could possibly explain the variance of the dependent variable: Does the PMB report on its sustainability performance through a SR? Table 4.1 presents an overview of all variables in play and their relevant measurement levels. The dependent variable ‘SR’ consists of five ordinal answer categories and has been defined based on exploratory research (Geerts & Dooms, 2017) and confirmed by the IAPH as well as representatives of the Port of Antwerp. We have opted to define the variables ‘SIZE’ and ‘FIN’ with an ordinal scale as this helped to increase the response rate (see also Section 4.2). The ordinal variable ‘DATA’ contains four answer categories, each referring to a certain period and completeness of performance data gathering. The construction of the variable ‘STAKEH’ is based on an adapted version of the stakeholder model of Friedman and Miles (2006) (see Appendix, Section 4.8). Last, the variable ‘SUST’ is constructed as a sum of selected answers from a list of options to which a weight was added in order to differentiate, based on the value they add to the general concept of sustainability. Three arguments led to the allocation of a higher weight to the answer options: 1) when voluntary willingness forms the basis of the sustainability initiative, 2) when the sustainability initiative is linked to and/or has an effect on the core activities of the PMB, 3) when external stakeholders are included. The measurement level of all other variables is more straightforward.

For the second part of the analysis (Section 4.5.3) we make use of descriptive association techniques (e.g. boxplots, etc.) to find possible relationships between organizational characteristics of PMBs (defined by the independent variables of Table 4.1) and the dominance of institutional pressures in play. The latter has been captured by a specific question of which the answer categories serve as proxies for the different well-known institutional isomorphisms, i.e. multinomial variable. We are aware that applying such an ‘ad hoc’ taxonomy can create a feeling of subjectivity. Nevertheless, using this taxonomy allows us to establish an exploratory format to test microlevel variables against macrolevel phenomena.

4.2 Survey design and data collection

All data used for this research has been provided by the PMBs themselves and assembled by making use of an online survey of which the questions are built upon the literature review and exploratory interviews with experts in the port environment in order to assure the content validity. The use of a survey was a deliberately choice for three reasons (Van Selm & Jankowski, 2006). First, it allows obtaining more managerial-driven information on the initiation of sustainability (reporting) compared to a content analysis of reports in which only pure facts that are available for the public can be observed and analyzed. The focus of the research lies on discovering more in-depth latent forces. Second, it helps the recruitment of respondents as the option of anonymity offered by an anonymous online survey is believed to create an environment in which sharing of experiences and opinions is facilitated. Third, as the study intents to cover a global scale, online surveys offer a certain ease in reaching this range.

The structure of the questionnaire starts with two general questions concerning the uniform understanding and interpretation of the concepts of sustainability and sustainability reporting, followed by questions probing for the PMB’s views on sustainability performance, strategy and reporting and ended with some high-level PMB profile questions. All questions are posed in a way that it would allow us to allocate the right information to each of the hypotheses formulated in the literature review. Furthermore, questions were expressed as close-ended affirmations for two reasons: 1) to improve the anonymity of the organizations and 2) to increase the chance of reaching a high response rate (Kelley et al., 2003). As the sector of PMBs is of limited size and in the case of open-ended constructions, it would possibly lead to the identification of some of them (e.g. there is only a small amount of very large PMBs in each region), which in turn would highly negatively influence the response rate. To even further increase the rate of response, we translated the survey into French, Spanish and Chinese. Encoding the survey into an online version was accomplished by making use of the software program ‘Qualtrics’. The questionnaire was verified in multiple phases by the representatives of the IAPH with modifications added after each phase before final validation.

The survey launch was presented during the annual conference of the IAPH in May 2019 and was thereafter promoted through their several social media channels. We also directly approached representatives of PMBs and other experts within and out of the own network via email, professional networks such as LinkedIn and cold calls. Furthermore, we also obtained the endorsement of several institutions and organizations in the industry who shared or promoted the survey to members (e.g. MEDports), as well as the support of individuals reaching out to their own network. The objective was to reach and collect completed surveys from representatives of PMBs around the world, thereby also limiting selection bias. The introduction prior the survey stated that the representatives in question should have an understanding of the concepts of sustainability (reporting) and a feeling of the present situation of the PMB on those topics. The online survey remained open for six months (from May 2019 to October 2019) during which several reminders were sent out. By the attempt of this study to examine a global sample and take into account a multitude of possible explanatory influences, we fill up the gap in earlier research mainly focusing on sustainability reporting in single contexts or on partial explanations of the phenomenon.

4.3 Statistical models and data analysis

The dependent variable, i.e. practice of sustainability reporting, measures five distinct categories, with the number of observations in each category ranging between 12 and 26. Originally, we wanted to apply a multinomial logistic regression based on the five answer categories of the dependent variable. However, a logistic model containing few numbers of events per variable can result in undesired consequences such as convergence problems, biased regression coefficients, and misleading conclusions (Peduzzi et al., 1996; Vittingho & Mc-Culloch, 2007). In order to increase the robustness and validity of the model, we rescaled the outcome variable to a binary variable consisting of the following two categories: 1) producing any format of a SR or 2) not producing anything at all. In order to present a complete and truthful picture, a stepwise forward model selecting procedure was performed to find the most parsimonious logistic model explaining the majority of variance of the data, while in the same process also checking for multicollinearity via the relevant VIFs. Models with few variables have the advantage to be numerically more stable, avoid overfitting the data, generalize better (as they depend less on the observed data) and have smaller standard errors. Stability of the obtained results was checked with a backwards and stepwise variable selection method, resulting in identical conclusions. All statistical analyses were performed using R (R Development Core Team, 2019). The stepwise variable selection methods are performed with the step()-function of the MASS-package (Venables & Riple, 2002). This function uses the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) to estimate the quality of each model, relative to each of the other models. Furthermore, graphs are created using the R-package ggplot2 (Wickham, 2016).

5. Results and discussion

Prior the larger analysis, focusing on the two large sections, descriptive statistics are used to showcase the distribution of the PMBs’ profiles of which completed surveys are received.

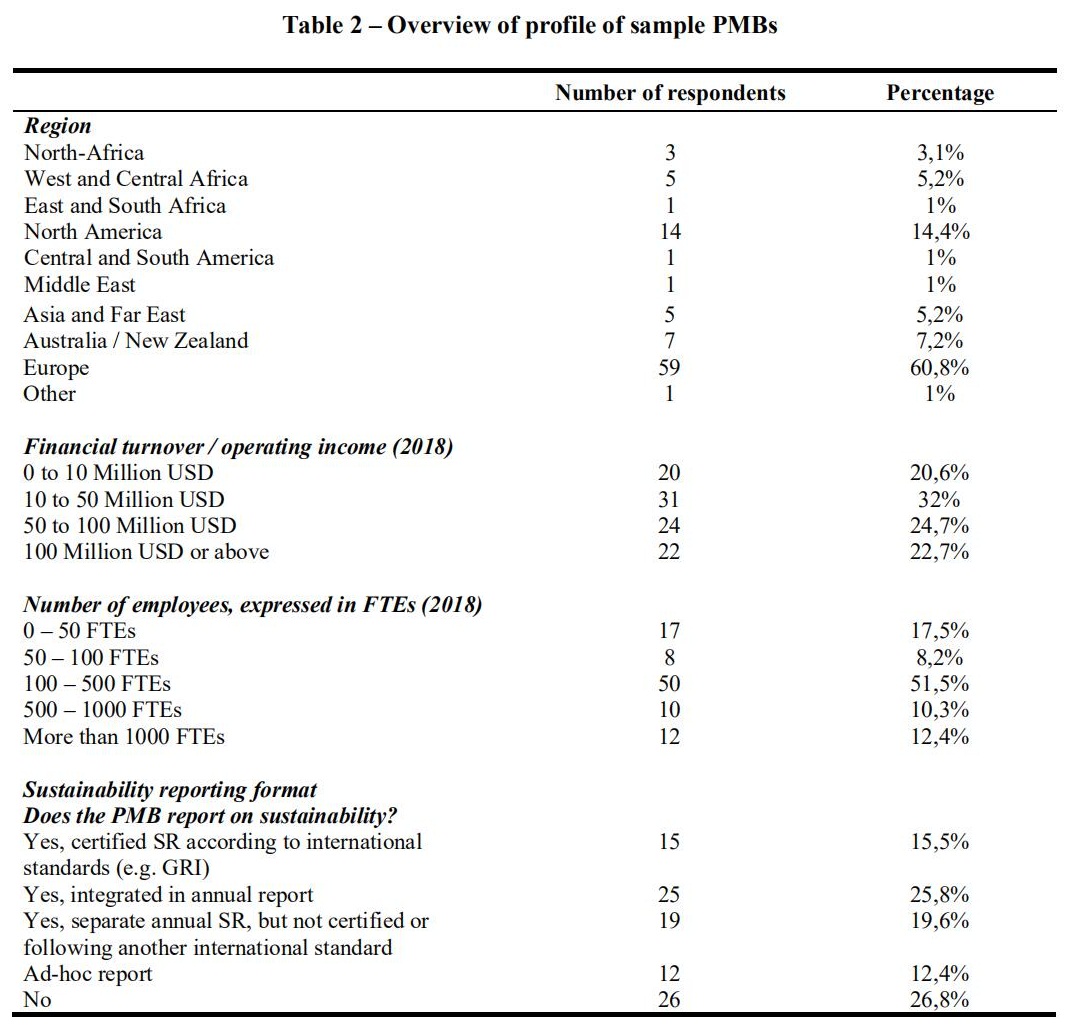

5.1 Profile of sample PMBs

In total, 97 fully completed and valid surveys were recorded. Given the nature of the applied data collection method, an online survey, and the business-to-business sector, we can state that the response rate is a more than reasonable result for this industry. Other studies in the same domain and relying on a survey encountered the same challenges and response rate (Ashrafi et al., 2019; van der Lugt, de Langen & Hagdorn, 2015). The respondents’ profiles show a variety based on region, size and governance model. Table 2 shows that PMBs located in the regions of Africa, Central and South America and Asia and Middle East were the least willing to fill out the survey. The answer categories containing only 1 answer were eventually deleted in light of fulfilling the condition of robustness of the further statistical analysis (see Section 4.4.3), with the exception of Africa for which we integrated all answers into one answer category. We are aware that the continuation of the analysis and interpretation of the results should be made with a certain caution as the underrepresentation of developing regions may result in a bias towards developed countries. Furthermore, there is an equal distribution when looking at the financial turnover of the PMBs, and a more or less normal distribution when analyzing the number of employees. Finally, when looking at the answers regarding the format of sustainability reporting (taking account of the five original categories), we observe an equal distribution. The sample of analysis is thus a reliable reflection of all possible real-life scenarios, reducing the risk of self-selection bias. The fact that even still 25% of all respondents do not report anything (yet) is already an interesting finding on itself as it shows that the practice of sustainability reporting follows a similar path as the innovation adaption lifecycle with PMBs as either innovators, early adopters or laggards, and that the practice of sustainability reporting is not yet fully institutionalized (Diederen et al., 2003; Westerman, McFarlan & Lansiti, 2006). However, the received answers are equally distributed over the different answer categories concerning the adopted format of reporting, ranging from ‘no SR’ to ‘fully integrated or GRI certified SR’. In the next section of the chapter, we will investigate if there are specific internal and/or external characteristics that could explain the difference in adoption behavior.

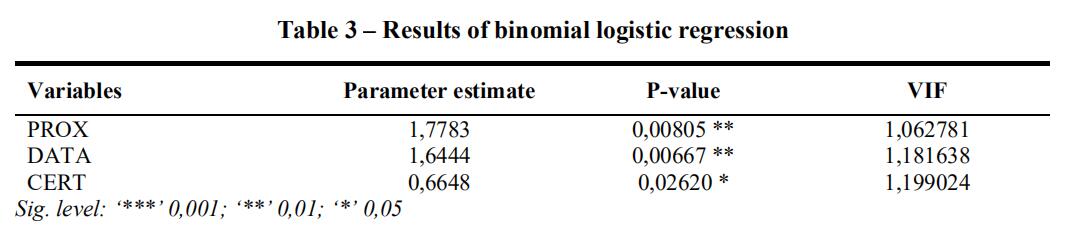

5.2 Determinants of sustainability reporting

As our results were realized using different variable selection methods while always checking for multicollinearity at the same time, we claim that we were able to identify those variables that actually have the largest impact on the practice of sustainability reporting. The outcome of this analysis is presented in Table 3, showing the three variables that create the model with the highest quality. Interesting to notice is that the well-known determinants such as size, financial turnover and level of autonomy, investigated in previous studies, do not seem to be significant enough when including all variables into one and the same analysis. Two reasons can potentially explain this result. The first being the fact that in general other parameters seem to have a larger explanation power. The second being the fact that probably the value of size and financial turnover have decreased in recent times, highlighting a tendency in which sustainability reporting is not only understood and embraced anymore by the larger PMBs but also by the small and medium-sized players. This is confirmed by anecdotal evidence such as the active participation of smaller ports in industry task forces on the harmonization of sustainability reporting for ports (e.g. the IAPH-PIANC workgroup 174 on the topic).

Looking at the results of the analysis in Table 4.3, we observe two variables ‘DATA’ and ‘CERT’ that are under the direct control of the PMB in terms of strategic decision-making and resource allocation and one variable ‘PROX’ being a fixed organizational characteristic (or natural factor condition as it relates to geographical location). For the latter, it can be stated that the odds of producing a SR is estimated to be almost six times (exp(1,7783) = 5,920) larger for PMBs located nearby a city than for those that are not close to a city, all other predictors held constant. The significance of this variable can be explained by the amount of stakeholder pressure the PMB effectively needs to deal with. Or, as the data of the variable is based on a ‘yes/no’ question, the significance can also be explained by the PMB’s perception of being closely located to the city and thus having a sense of responsibility towards the community. In general, the closer a port is located to densely populated urban regions, the more likely the PMB will need to defend the presence of the port towards several stakeholder groups, given the external effects of port activities. As previous research has already shown, producing a SR can help in the mitigation of this pressure as such a report can serve as a formal commitment that the PMB takes the concerns and needs of the stakeholders in question seriously. The need for intense stakeholder interaction to manage expectations can be partially covered by the development of a SR.

Next, the variable ‘DATA’ teaches us that for PMBs that have a stronger history of data gathering the odds for having a SR are higher. When a PMB decides to consistently invest in measuring and monitoring processes, structures and models to keep track of the progress regarding its TBL dimensions, it acknowledges the value this kind of longitudinal information has, not only in terms of complying with sustainability development goals but also in terms of risk management. The availability of multidimensional information can lead to a decrease in overall costs, as risks can more easily and proactively be identified leading to better damage control management, as well as proactively formulating strategies to improve sustainability performance. In other words, the PMB exhibits a structured blueprint for frequently creating a SR.

Last, PMBs that have more social/environmental certifications are more likely to produce a SR, all other parameters held constant more. From our results, it appears that the willingness to comply with certain social and environmental certifications can be regarded as a sort of first step into developing an overall sustainability strategy. It counts as a proxy, an indication for the likelihood to develop a SR. However, based on observed real-life behavior, e.g. by the Port of Antwerp, we know that the interaction in the other direction does not always hold. More in particular, while the Port of Antwerp was an early adopter of certifications, through time the Port of Antwerp has decided not to pursue several certifications anymore as these do not always request the same level of information detail and scope compared to the information the PMB tries to pursue on a daily basis and through its SR. In other words, the implementation of a SR substitutes the certifications as a means to show the tangible commitments of the PMB to its community of stakeholders when it comes to sustainability. These results suggest that developing a SR is not just a stand-alone practice with the sole objective to ‘please’, but that it is part of a longer-term, larger strategy of doing business shown by the significance of the variables ‘DATA’ and ‘CERT’.

5.3 Associations between port characteristics (internal factors) and institutional environment (contextual factors)

Through this analysis we want to discover if certain organizational characteristics are associated with one or more institutional isomorphisms. In other words, which combinations of organizational characteristics and institutional pressures occur together more often than others? The most interesting and value-adding results are shown and discussed in the following paragraphs.

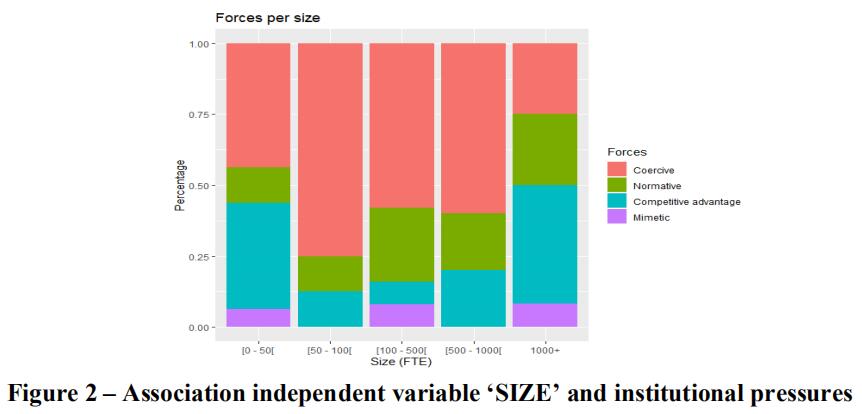

Looking at the first variable ‘SIZE’ (Figure 2), we notice a very high presence of the isomorphisms ‘competitive advantage’ and ‘normative’ for the largest PMBs, i.e. more than 1.000 FTEs. This means that the largest PMBs proactively acted and started reporting out of strong beliefs in either the competitive benefits of reporting or out of moral norms and values towards reaching a sustainable future. Also, the category of smaller ports deserves our attention. Compared to what intuitively would be thought, i.e. ‘mimetic’ isomorphism, this category also shows a high presence of the ‘competitive advantage’ isomorphism. Even more, this category consists of 20% of the total respondents. This outcome can be explained by the fact that small PMBs do not have the same bargaining power towards the external environment as the larger ones have (often these are dominant economic actors in a region), meaning in their acting they are more dependent on how society perceives the presence and sustainable added value of the port. Following this reasoning, those PMBs are very aware of the power (competitive advantage) of a SR. According to the results, medium-sized PMBs are rather driven by the ‘coercive’ isomorphism, i.e. developing a SR out of pressure to conform to legal requirements or out of reputational objectives. Similar results can be observed for the variables ‘FIN’ and ‘DATA’, possibly explained by the fact that all three variables are indirectly linked with the same underlying factor ‘availability of resources’.

A second result, shown in Figure 3, is that the ‘normative’ isomorphism is not present in more developing/emerging countries/regions such as Africa and Asia. In those regions sustainability reporting is still often a question of availability of resources. The total cost-benefit balance of certain sustainability actions will outweigh the moral balance.

Third, there does not seem to be evidence of a strong association between the number of social/environmental certifications achieved by the PMB and the ‘normative’ isomorphism (Figure 4). In other words, pursuing these certifications appears to be a conscious strategic decision on organizational level, independently of the kind of underlying pressure.

Figure 5 displaying the variable ‘SUST’ against the different isomorphisms clearly shows that PMBs that put efforts into developing organization-wide sustainability initiatives and that try to make the concept of sustainability part of the larger organizational structure and thinking, regard the initiation of sustainability reporting as an obligatory step in pursuing a normative differentiation strategy. The latent ‘normative’ pressure will play a role for PMBs that, in general, already have a high awareness for sustainable development. The amount of sustainability initiatives undertaken and the organizational levels to which they are implemented is a reflection to which extent the concept of sustainability is incorporated into the ‘DNA of a company’.

Furthermore, Figure 6 displays a clear association between a high level of stakeholder inclusion during the general strategy planning of PMBs and the force ‘competitive advantage’ as a decisive factor to start reporting. An increasing amount of PMBs acknowledge the importance of substantive and high-quality stakeholder inclusion, as aligning the organization with the stakeholders’ expectations can help in safeguarding their license to operate. The development of a SR can contribute to this longer-term strategic objective. Only when stakeholders are consulted to a high degree and on an ongoing basis, the content of a report is not only showing what the PMB believes people want to know but will show those issues (both positive and/or negative) that are regarded as material by the stakeholders themselves, leading to high societal acceptance of the PMB.

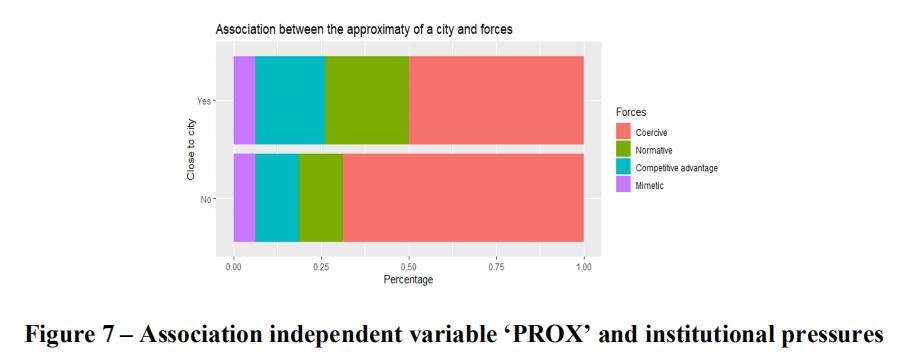

Following the same reasoning, we observe that for PMBs located nearby cities and thus confronted with higher levels of stakeholder pressure, the ‘normative’ and ‘competitive advantage’ isomorphisms are more present, compared to those PMBs not located nearby cities (Figure 7).

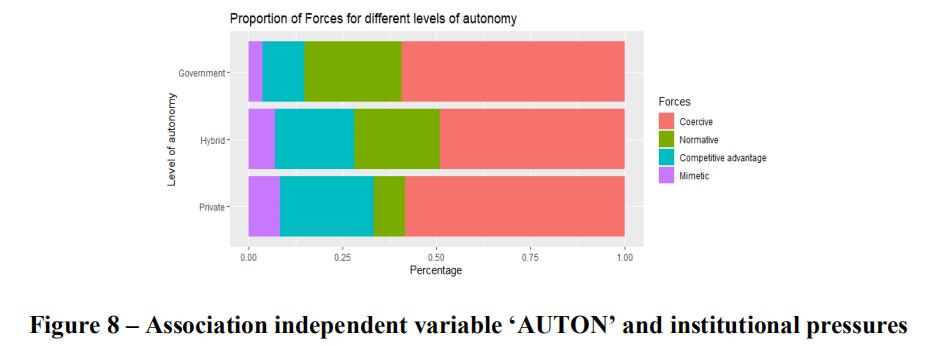

Finally, the last figure (Figure 8) shows that government-controlled PMBs with a lesser degree of managerial autonomy have started reporting about sustainability from a ‘normative’ point of view, i.e. from the need to pursue what is desirable and right for society, compared to more privately owned structures that were led by the ‘competitive advantage’ of the practice, i.e. sustainability reporting as added value from a ‘cost-benefit analysis’ perspective. The outcomes for more hybrid structures, being the mix of both autonomy governance models, interestingly shows exactly the average results of the two extremes, confirming the relevance of the continuum ‘public-hybrid-private’ in terms of ownership and autonomy for PMB related research.

5.4 Policy and managerial recommendations)

Based on our research, we identify two major policy and managerial implications/recommendations, the first with a focus on PMBs and the second on environmental certification bodies such as ECOPORTS, GreenMarine, etc.

(1) Given that PMBs are part of a larger port cluster, one can question what the boundary setting of indicators of a SR should be, in particular knowing that the history of performance data gathering is identified as both a significant explanatory variable, as well as, more implicitly, a barrier to engage in sustainability reporting. Should reporting be limited to the exclusive organizational characteristics and responsibilities of the PMB itself, or should this also include overall cluster and supply chain performance, and to what extent? An important concept underlying this question is the need for knowledge and data transfer specifically with a focus on sustainability practices and reporting, which appears to be no common practice (yet) in the port industry at present (Langenus & Dooms, 2015). In order to reach a sensitization on the industry level of the opportunities and benefits linked to industry-wide sustainability reporting, it is important that each individual PMB acknowledges the importance of investments in proper data collection and monitoring, as well as in strong trust relationship building among the different stakeholders of the port cluster. This requires a set of capabilities in terms of trust building with stakeholders (to obtain data), investment in IT systems (for efficient and trustworthy management of data) and Human Resources (data analysts). However, the research presented in this chapter shows that it is not specifically a matter of mobilizing those ports with a smaller resource basis as several already show promising first steps. It appears to be more a matter of adapting the existing organizational culture, norms and beliefs within the port industry in general.

(2) In order for voluntary self-evaluation based certification schemes to continue to exist it is important that they continue to position themselves as one of the ‘best practices’ in the domain of sustainability strategies. The more PMBs adopt the practice of sustainability reporting, and report on outcomes rather than compliance with social and environmental management standards, the higher the chance a SR will be considered as a general standard in sustainability strategy thinking. Towards stakeholders, a SR often covers in greater detail and thus in a more convincing way the same aspects of these certifications, therefore significantly lowering the added value of the certification. Specifically, when the SR is developed in collaboration with the PMB’s relevant stakeholders and thus paying attention to their social and environmental demands and needs. In sum, the practice of certification might lose relevance when the necessary time and investment in obtaining the certification will not be outweighed by (non- )economic benefits compared to those of sustainability reporting.

6. Conclusion

This study investigates, on a global scale, the dynamic of internal (organizational characteristics) and external (institutional environment) factors that would positively/negatively influence the practice of sustainability reporting by port managing bodies. It is the first study of this size in the domain of PMBs that incorporates all existing internal determinants into one regression analysis in order to discover those organizational characteristics that are most important, compared to other studies where often only national contexts or a limited set of variables have been analyzed. Furthermore, it is also the first study concerning sustainability reporting that analyzes the institutional environment in which PMBs operate and in turn, links these insights with the outcome of the regression analysis in order to maximally reveal the driving mechanisms behind sustainability reporting in the port sector.

Based on the obtained results of a global survey with port managers as targeted audience, a set of conclusions can be drawn. First, the most significant organizational determinants to start reporting about sustainability are: (i) proximity to a city, (ii) history of data gathering, and (iii) amount of obtained social/environmental certifications. The latter two are elements over which the PMB has large control in terms of strategic decision-making and resource allocation. This strengthens the idea that engaging in sustainability reporting is the objectivation of an initial shift in mindset towards a more social and environmental responsible plan of action and not just the result of pure economic rationale.

Second, the institutional context in which the PMB operates is as important as its organizational characteristics. Institutional pressures appear to have large and diverse influences on the decision-making of PMBs with regard to SR adoption. However, as the results show, there is no significant unambiguous interaction between certain organizational characteristics and institutional pressures. This relationship appears to be much more complex so that we can only identify more common combinations of internal characteristics and external pressures, highlighting the fact that full convergence in sustainability reporting on a global level is not yet achieved. Stated differently, at present, the practice of sustainability reporting is not yet fully institutionalized, while recognizing the existence of multiple ‘fields’. The results of our research confirm a great diversity and undermine the idea of ‘one approach fits all’ for PMBs.

Third, at present, institutionalization of sustainability reporting applies to the activity rather than the content of it, given the wide variety of approaches, subject to certification or not. Reaching full consensus on the process and content of a SR and thus the option of benchmarking is still in its infancy phase.

The primary limitation of our research arises from the relatively small sample size, partially explained by the nature of the applied data collection method, an online survey, and the focal organization of our analysis, PMBs. The ratio of the number of respondents and included variables into the analysis was relatively low, limiting the applicability of more sophisticated regression analyses. It is therefore difficult to establish whether the other tested variables are not significant, because of the limited amount of observations or because of the small explanation power of the variable. Further research, enlarging the sample, could clarify this doubt. Furthermore, the respondents are mostly all part of developed countries. Unfortunately, no answers were received from Central and South America, and limited responses were received from Asia and Africa. However, the received answers are equally distributed over the different answer categories concerning the adopted format of reporting, ranging from ‘no SR’ to ‘fully integrated or GRI certified SR’. The sample of analysis is thus a reliable reflection of all possible real-life scenarios. However, further research should include more ports from the other developing regions, as these will have different institutional environments and organizational characteristics, potentially leading to different outcomes. Another point that requires critical caution, is that of applied definitions and indicators as proxies for the analyzed determinants. For example, in this study, we use the indicator ‘financial turnover’ as proxy for the variable ‘financial capability’ as there is currently no other commonly accepted indicator under the form of e.g. profitability for PMBs. Finally, supplementary interviews could further enrich the results of the research.

RECOMMENDATION